About two weeks ago I received a phone call from Steve Earis. He’s a fellow wood turner, earning his living from making skittle sets and exercise clubs. He had picked up a post from somebody on arbtalk, about a 5t sycamore coming down somewhere in Birmingham and anybody interested could give him a call and have some.

So I give this guy a call, and he’s a little nervous. Turns out he’s previously been burned by another wood turner who not only had not lived up to promises made, but also left him with a mess to clean up. But that’s a story for another day.

I got there next day in the morning, and the tree was down already, but still in one piece. After a little negotiation and a £40 donation to the charity they work for, they cut the trunk into two sections about 3ft long each (trunk diameter was just under 3 ft) and cut these into slabs 4-6″ thick. I had to make three trips with my car to get it all home.

Already when the first slab came off the tree I could see this was going to be good. But it got better. At first I thought that there might be a bit of rippling/curling going on, and I was just happy to get my hands on some nice big chunks of wood. You know, the sort of thickness you hardly ever get from a timber place.

Already when the first slab came off the tree I could see this was going to be good. But it got better. At first I thought that there might be a bit of rippling/curling going on, and I was just happy to get my hands on some nice big chunks of wood. You know, the sort of thickness you hardly ever get from a timber place.

But the more these guys cut off the trunk, the more I realised that there was ripples everywhere. In some places you can even see it right through the bark. Malcolm Thorpe, a fellow club member at the West Midlands Turners, reckons this is because Acers are not the strongest trees in the world, and once the size goes beyond a certain limit, especially if the tree has grown fast, it essentially buckles under its own weight. OK, this tree has grown fast. I counted the rings on one segment, and this tree was certainly no older than max. 80 years, probably only about 60 years. Most of the rings are 2-3 mm wide, but some of them are well over 5mm, and that is fast growth for any tree. Ash trees grow similarly fast, and unsurprisingly they also have a lot of curling going on in older trees. It’s just that ash trees firstly hardly ever get to 100 years because the die on the inside (creating olive ash) and then get cut down or keel over in the next storm, and secondly otherwise the emerald ash borer gets them (ash dieback desease).

So now I had two piles of Sycamore in the garden. I’d sealed the end grain with PVA, and stickered them, as can be seen on the picture. Most of the pieces were so heavy I could barely manoeuvre them around, let alone lift them. And then somebody on the AWGB forum mentioned I should treat them with a mild borax solution to prevent infection with grey stain. Apparently this is something very common with sycamores.

So now I had two piles of Sycamore in the garden. I’d sealed the end grain with PVA, and stickered them, as can be seen on the picture. Most of the pieces were so heavy I could barely manoeuvre them around, let alone lift them. And then somebody on the AWGB forum mentioned I should treat them with a mild borax solution to prevent infection with grey stain. Apparently this is something very common with sycamores.

I ordered the borax from ebay (can’t buy it in the UK any longer), and then spent all day on Friday cutting the slabs into more manageable sizes, either by cutting them into thinner slabs (for big plates) or chunks of less width (hollow forms, bowls, etc.) Since most of them had the bark still on, and went right to the outside of the tree, they didn’t want to stand on their sides, so I made myself some simple jigs to hold them upright while I was busy with the chainsaw. These worked a treat, and I’ll probably publish a separate HowTo article on them some time.

I ordered the borax from ebay (can’t buy it in the UK any longer), and then spent all day on Friday cutting the slabs into more manageable sizes, either by cutting them into thinner slabs (for big plates) or chunks of less width (hollow forms, bowls, etc.) Since most of them had the bark still on, and went right to the outside of the tree, they didn’t want to stand on their sides, so I made myself some simple jigs to hold them upright while I was busy with the chainsaw. These worked a treat, and I’ll probably publish a separate HowTo article on them some time.

This really took my poor electric chainsaw to the limit. Some of the slabs were close to 30″ wide, and my blade is only 16″ long, It had to work very hard for this, and I think it took some umbrage. The motor now sounds distinctly different, and the blade has started to wiggle a little, even when all screws are tight.

And then there were the nails. I have no idea what it is that drives people into putting nails into live trees. Must be the sadist in them. I knew there were going to be nails, because a few were found already when the original slabs were cut from the trunk. But I found loads more. And these are just the ones I went through with the chainsaw. No doubt there will be more. As you can see, I ruined one chain completely. Some of the teeth have broken off, and the chain came off the blade and that ruined the runners. Luckily I have a spare chain, and could finish the job.

And then there were the nails. I have no idea what it is that drives people into putting nails into live trees. Must be the sadist in them. I knew there were going to be nails, because a few were found already when the original slabs were cut from the trunk. But I found loads more. And these are just the ones I went through with the chainsaw. No doubt there will be more. As you can see, I ruined one chain completely. Some of the teeth have broken off, and the chain came off the blade and that ruined the runners. Luckily I have a spare chain, and could finish the job.

I then used my electric hand plane to make the surfaces as smooth and flat as I thought was reasonable. I reckoned that way it would be easier to apply the borax, and also expose a lot less surface to any new fungal spores and other nasties. The pic showing the jig above was taken quite early on in the day, and by the end of the day the shopfloor was covered all over 6″ deep in shavings (and it’s a big shop). I reckon all in all I produced about 100kg of shavings and waste pieces. This is all down to the fact that the original slabs were not cut with any particular care, since the guy was mostly concerned with getting it done quickly, without realizing the extra waste he was producing, and in consequence there were loads of misalignments of cuts. Never mind, all the shavings are going to Helen’s horses, and the cutoffs are going to Cathy’s wood burner. Nothing wasted.

What I discovered during all this activity was that

What I discovered during all this activity was that

- The ripples are everywhere, except for the very core of the tree. This is consistent with Malcolm’s theory, since the young tree would have had the strength to support its own weight and therefore not develop ripples.

- The upper part of the trunk was cut off right at the point of the first major crotch, and right beneath that crotch is some of the most beautiful figure I have ever seen (see image).

- The grey stain was already having a go, and hopefully I managed to cut most of it off and kill the rest with the borax. Would be a shame otherwise.

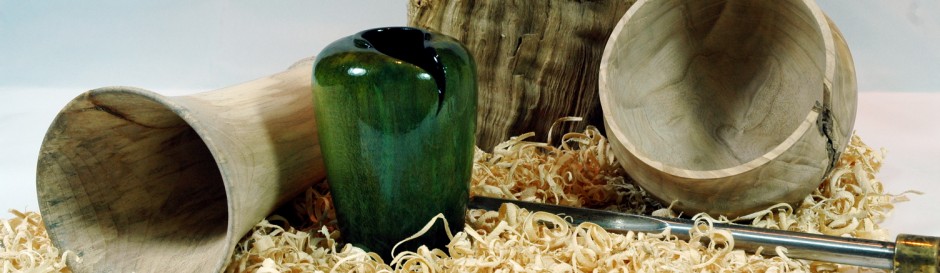

- There are places where the wood inside the tree is effectively green! See image.

So now this is all sealed and treated and stacked and stickered in the garage. The pile is about my height, and I reckon there is about a ton of the finest rippled/flamed/curly/fiddleback/younameit sycamore, and all of it for £40, 3 trips to Birmingham, and 3 days of hard work. OTOH, one of the big slabs, which is about 6″ thick. will easily yield enough material for at least a dozen guitar body sets, and they sell for about £60 a pop. That’ll be £720, possibly more. In a few years time, since it has to dry out first.

So now this is all sealed and treated and stacked and stickered in the garage. The pile is about my height, and I reckon there is about a ton of the finest rippled/flamed/curly/fiddleback/younameit sycamore, and all of it for £40, 3 trips to Birmingham, and 3 days of hard work. OTOH, one of the big slabs, which is about 6″ thick. will easily yield enough material for at least a dozen guitar body sets, and they sell for about £60 a pop. That’ll be £720, possibly more. In a few years time, since it has to dry out first.

So, all in all, I did have to put some time and effort into it, but in the end it was down to Steve Earis being a good friend, and just plain old good luck.